Since student engagement is a leading indicator of academic achievement and persistence in school as well as a key element of school climate, educators can greatly benefit from measuring it. So, what does student engagement look like, according to the students themselves?

To understand how engaged students are feeling in school, YouthTruth analyzed survey responses from over 230,000 students in grades three through twelve. The data was gathered between November 2012 and June 2017 through YouthTruth’s anonymous online climate and culture survey, administered in partnership with school districts and charter management organizations across 36 states. Our analysis looked at a subset of questions related to student engagement and uncovered some key insights.

Across all grade levels, the majority of students feel engaged.

The majority of students report feeling engaged in school. However, when we compare student responses by grade level, elementary students are slightly more likely to feel engaged than secondary students, with 78 percent of elementary students feeling engaged. For secondary students, the proportion drops to 59 percent of middle schoolers and 60 percent of high schoolers feeling engaged. While still the majority, that leaves considerable room for improvement.

The data also reveal variation across school sizes. Across the secondary grade levels, students at small schools are slightly more likely to feel engaged than their peers at medium and large size schools. (In our analysis, small schools are defined as high schools with 300 or fewer students and middle schools with 200 or fewer students, while large schools are defined as high schools with 1200 or more students and middle schools with 800 or more students.)

This finding echoes findings from previous studies on small schools, which have shown that students in small schools tend to have better attendance rates, lower dropout rates, higher grade-point averages, and higher high school graduation rates. Proponents of small schools argue that small high schools, in particular, are able to promote stronger academic rigor and personal relationships between students and staff, which helps engage students and enrich their experience.

Most students take pride in their schoolwork.

Across all secondary students, we find that most students take pride in the work they do in school. Seventy-two percent of middle school and 68 percent of high school students report that they take pride in their school work. It is encouraging to see that students care about the work they are producing.

There are some slight differences across students of demographic groups for this question. When examining responses by students’ self-reported gender identity, we see that students who identify as female are slightly more likely to take pride in their school work, and students who identify as other than male or female are slightly less likely to take pride in their school work.

At my school, you can find people with determination, passion, and time management, and it really pushes me to be a better student. Everyone really cares about their education, and it pushes me to work harder.

School is important to me, and I inspire myself every day to do well in school. Getting good grades and getting my work done makes me feel accomplished.”better student. Everyone really cares about their education, and it pushes me to work harder.

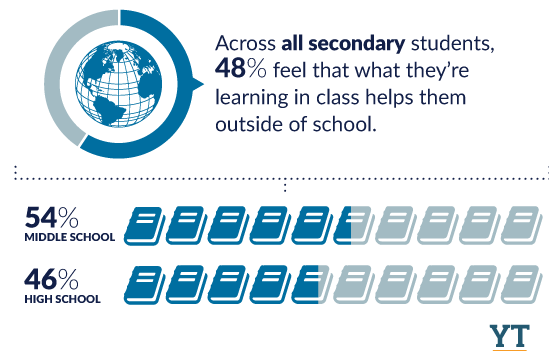

Less than half of secondary students feel that what they’re learning in class helps them outside of school.

While it is encouraging that the majority of students feel engaged overall, when it comes to relevance the results are concerning. Only 48 percent of secondary students feel that what they are learning in class helps them outside of school. With less than half of sixth through twelfth graders feeling their learning helps them outside of school, we can imagine hundreds of thousands of students across the country wondering, “When will I ever use this in real life?”

When we disaggregate the findings by level, high school students are slightly less likely than middle school students to feel that what they learn in class helps them outside of school. In other words, as students get closer to “the real world,” they are even less likely to feel their learning in school is pertinent to their outside lives.

PRACTITIONER STORY

One way to help students relate their academic work to daily life is to connect students with projects in their local community. “If you want students to do work connected to the world outside of school, you need to create places and spaces for those intersections,” says Tim McNamara, Director of High Tech High Chula Vista (HTHCV) in San Diego, CA.

Each year, HTHCV hosts a Community Networking Lunch where local nonprofit organizations, businesses, and community groups meet with teachers to share organizational challenges and brainstorm ideas for collaborative projects that students can undertake for school credit.

Teachers then design projects focused on issues that overlap with a community organization’s area of interest. In these community-centered, authentic projects students have the opportunity to work in teams to develop solutions that suit the community partner’s needs and address real-world issues and problems.

The final project is then exhibited publicly. By combining project based learning with cooperative community learning, students are making real-world connections, creating a professional network, and meeting academic learning goals.

For examples of HTHCV projects, visit www.hightechhigh.org/hthcv/projects.

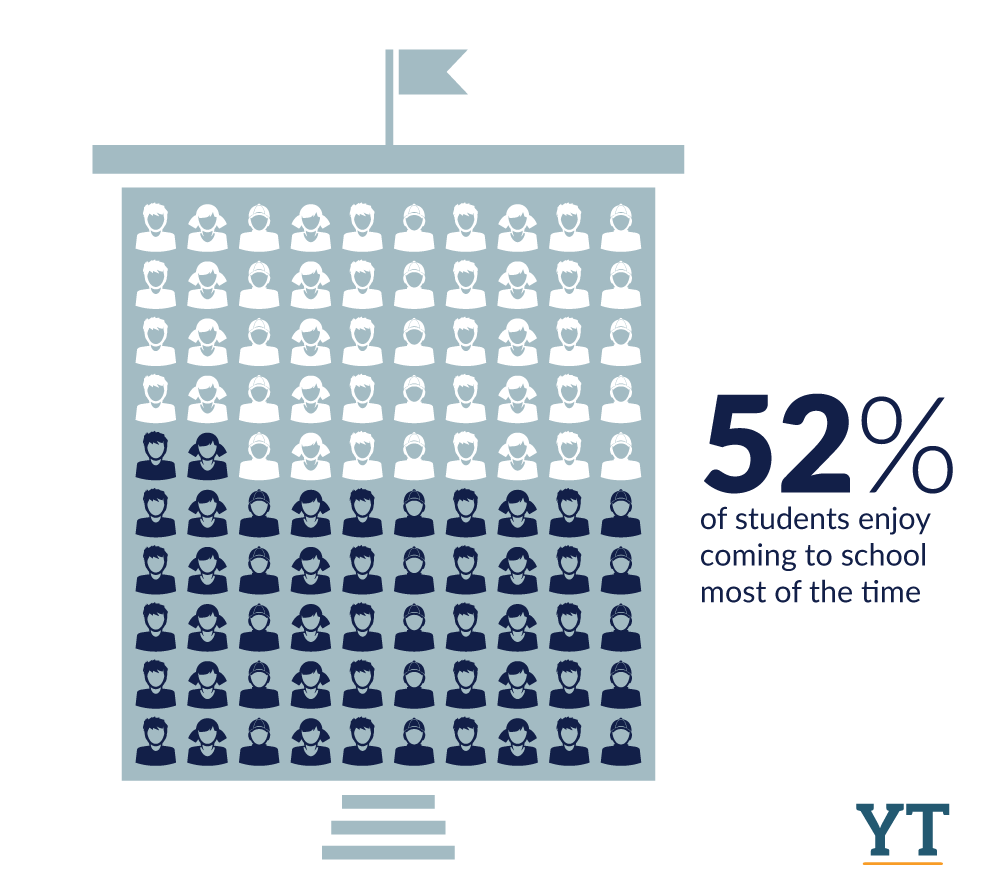

Only about half of secondary students enjoy coming to school most of the time.

Only 52 percent of secondary students enjoy coming to school most of the time. Given the recent national conversation about chronic absenteeism and its focus under many states ESSA plans, this finding is particularly concerning within the context of untangling why students may not be coming to school.

Students who are chronically absent – typically defined as those who miss at least 15 days of school or more in a year – may be missing school for a variety of reasons over which schools have little control, including poverty, health challenges, community violence, and difficult family circumstances. But building a school environment in which students enjoy coming to school is an important place to start.

Listening to students is important.

Research shows that student engagement is an important component of a positive school culture and is necessary for driving academic achievement. The first step in understanding and prioritizing student engagement is to measure it. As the saying goes, “what gets measured gets managed.” Without a measure of student engagement as a leading indicator, educators are limited to outcome data, like grades and attendance, which are much less useful once the student has stopped turning in assignments or coming to school.

Asking ─ and truly listening ─ to what students have to say about their unique experience as a learner is the best way to understand where to target improvements. Anonymous feedback from all students that is delivered to educators quickly is an efficient, effective, and affordable way to gather insights that make a difference in building a positive and engaging culture of learning.

Want to learn more about how you can gather student feedback to drive improvements in your school or district?

Other Resources

RESOURCES

- Cornell University – Center for Teaching Innovation

Resources for teachers at various stages of their teaching career to explore different methods for engaging students. - Edutopia – 4 Student Engagement Tips (From a Student)

Hear from one student how relationships, humor, choice, and displaying his work engaged him in learning. - Iowa State University – Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching

recommendations for creative techniques to engage students in discussions, problem-solving and critical thinking. - Marzano Research – The Highly Engaged Classroom

Designed to help students get an early indication of how much and what types of financial aid they would receive at specific schools. - University of Washington – Center for Teaching and Learning

Tools for teachers to help engage students in the learning process.

RESEARCH

- Berkowitz, Ruth, Hadass Moore, Ron Avi Astor, and Rami Benbenishty. “A research synthesis of the associations between socioeconomic background, inequality, school climate, and academic achievement.” Review of Educational Research 87, no. 2 (2017): 425-469.

- Finn, Jeremy D., Gina M. Pannozzo, and Kristin E. Voelkl. “Disruptive and inattentive-withdrawn behavior and achievement among fourth graders.” The Elementary School Journal 95, no. 5 (1995): 421-434.

- Finn, Jeremy D., and Donald A. Rock. “Academic success among students at risk for school failure.” Journal of applied psychology 82, no. 2 (1997): 221.

- Lee, Jung-Sook. “The relationship between student engagement and academic performance: Is it a myth or reality?.” The Journal of Educational Research 107, no. 3 (2014): 177-185.

- GUNUC, Selim. “The relationships between student engagement and their academic achievement.” International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications 5, no. 4 (2014): 216-231.

Closing the Feedback Loop: Sample Discussion Questions

- To what extent do you think these findings speak to the student experience at your school? Which findings seem most relevant?

- How do you think students’ feelings of engagement on your campus might be similar to or different from these findings?

What sources inform your hypothesis? - What is one area in which your school does well at engaging students?

- What is one area in which your school could work to better engage students?

- What programs or processes do you currently have in place for encouraging and talking about student engagement?

- To what extent do you think this data reflects the student experience at your school? Which findings seem most relevant?

- How engaged do you think you and your peers feel?

- Do you feel that what you’re learning in class helps you oustide of school? If not, do you have any ideas on how to make classes more relevant?

- Do you enjoy coming to school most of the time? Why or why not?

- What questions do you have after reflecting on the data?

DOWNLOAD THE FULL REPORT

To help educators, parents, education funders, and students understand how engaged students are feeling in U.S. schools, we went straight to the source for more insight. We analyzed survey responses from over 230,000 students in grades three through twelve through YouthTruth’s anonymous online climate and culture survey, administered in partnership with school districts and charter management organizations across 36 states. Download the full report to:

To help educators, parents, education funders, and students understand how engaged students are feeling in U.S. schools, we went straight to the source for more insight. We analyzed survey responses from over 230,000 students in grades three through twelve through YouthTruth’s anonymous online climate and culture survey, administered in partnership with school districts and charter management organizations across 36 states. Download the full report to:

- Understand how engaged students are feeling in schools across the United States

- Discover resources to take action

- Close the feedback loop with suggested discussion questions for principals, teachers, and professional learning communities as well as for teachers and principals in conversation with students