The COVID-19 pandemic has upended significant aspects of education in the United States. This report aims to help adults lead with compassion and curiosity about how the pandemic has affected students within K–12 education and answer the following questions: What do students have to say about learning and well-being in spring 2021, and what recommendations do students have about what to prioritize in the upcoming academic year? As we navigate the challenges of this moment and the days and months ahead, students’ voices must be central to our pandemic recovery efforts.

In Students’ Own Words

“I know these times are unprecedented, and no one really has known what to do, but the lack of change gives me, the student, an impression that you have given up on us.” “PLEASE LISTEN TO US!” “Do the right thing and plleeeaaaasssee do something. This is your best feedback that you are going to get, please listen to it and do something.” “I just had to get that off my chest. Please if someone reads this… hear out my ideas for school.” “Why even ask in the first place if you aren’t going to listen? I sincerely hope you understand what I’m saying, and where I’m coming from. Because I’m almost ready to just completely give up on getting an education. Do something. Make changes. Do better.”

High school qualitative composite narrative coded for “listen to me,” compiled from analysis of more than 270,000 open-ended responses in spring 2021.

Introduction

The Students Weigh In project reflects YouthTruth’s mission as we worked to listen and learn from the lived experience of youth during a wholly unusual era of schooling. Our hope is that these practical insights from students will inform educators, youth-serving organizations, policymakers, and funders to support students effectively and equitably in the upcoming school year and beyond.

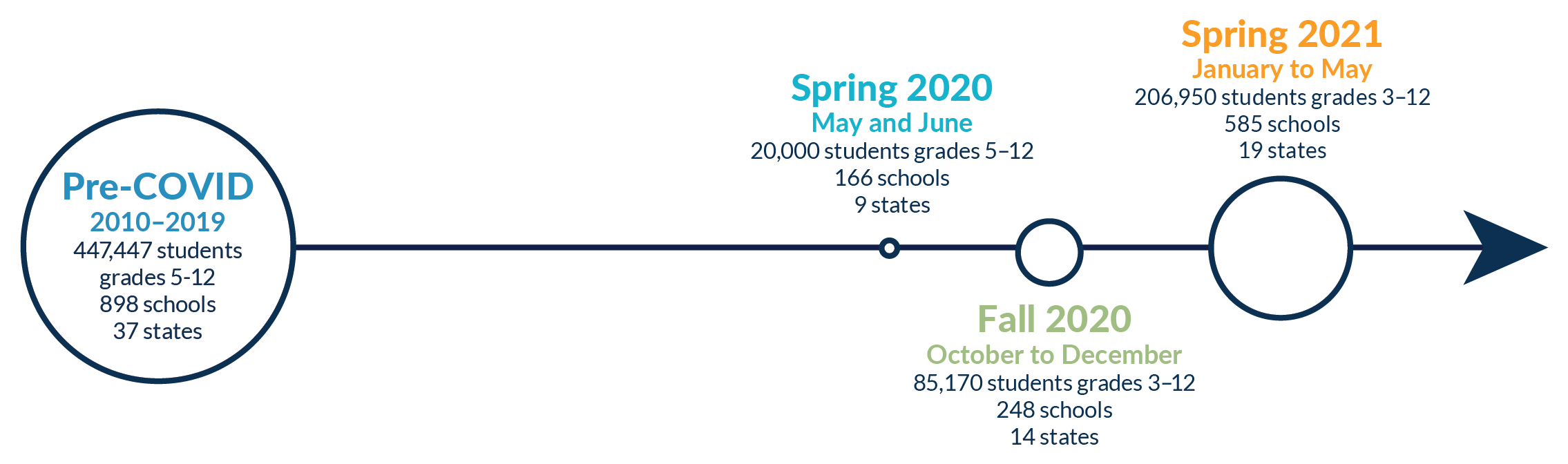

In this final report of our three-part Students Weigh In series, more than 200,000 students shared their experiences and feedback about learning and well-being in spring 2021. These insights build on YouthTruth survey findings from fall 2020, findings from emergency distance learning in spring 2020, as well as pre-COVID student voice insights from the decade prior to the pandemic.

Findings

While students’ perceptions of learning returned to pre-pandemic levels this spring, there is cause for concern about students’ social and emotional well-being. Students offer insights on how technology can help or hinder learning.

The overall number of obstacles to learning for students is down. However, inequitable experiences and compounding barriers persist, especially for Black and Latinx learners.

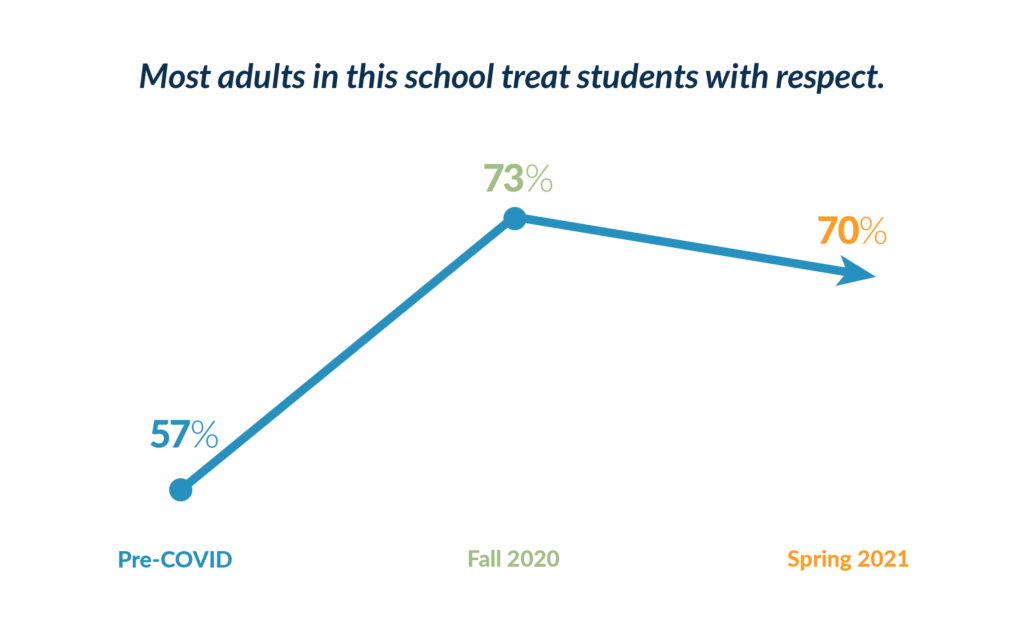

Students felt more respect from adults during the pandemic as well as increased academic support from teachers. However, respect and teacher support are experienced unevenly across student groups.

The ``COVID Effect``

The “COVID Effect”

We invite you to join us in considering how the experiences of this generation of students have been shaped by this historic period.

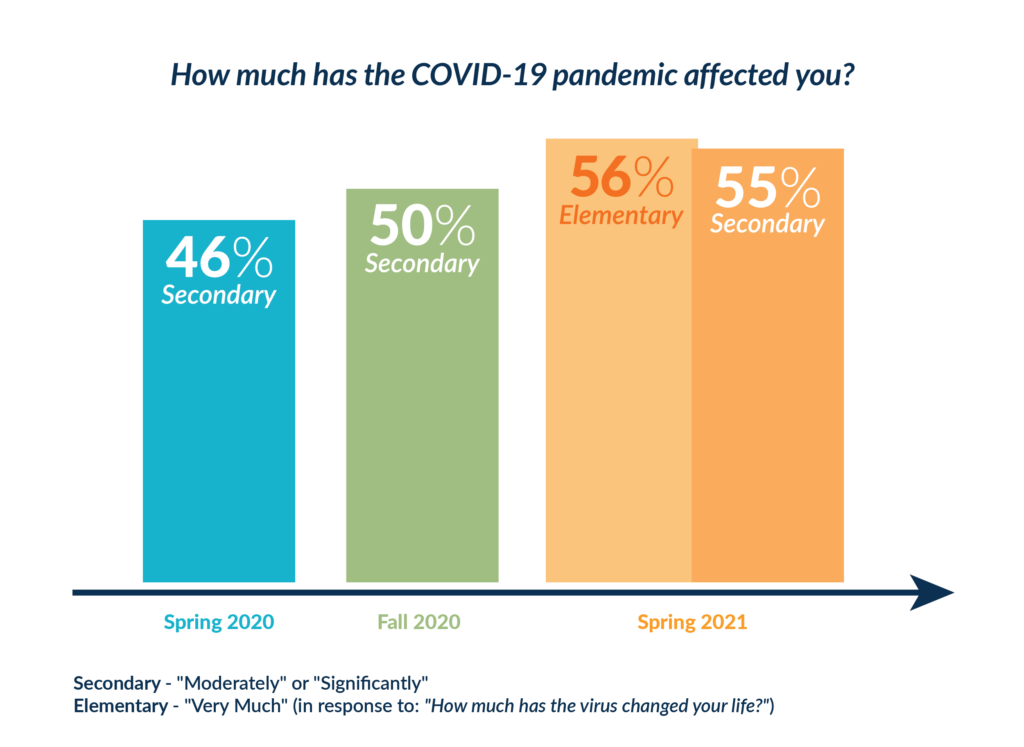

This spring, a greater percentage of secondary school students reported that COVID-19 had moderately or significantly affected them as compared to fall 2020 and to spring 2020. Fifty-five percent of secondary school students reported being moderately or significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. And 56 percent of elementary students (grades 3–5) in spring 2021 said that the virus has changed their life very much.

As you will learn in this report, students are emphatically asking to be heard, and they are imploring us all to do better.

Survey Sample

Survey Sample

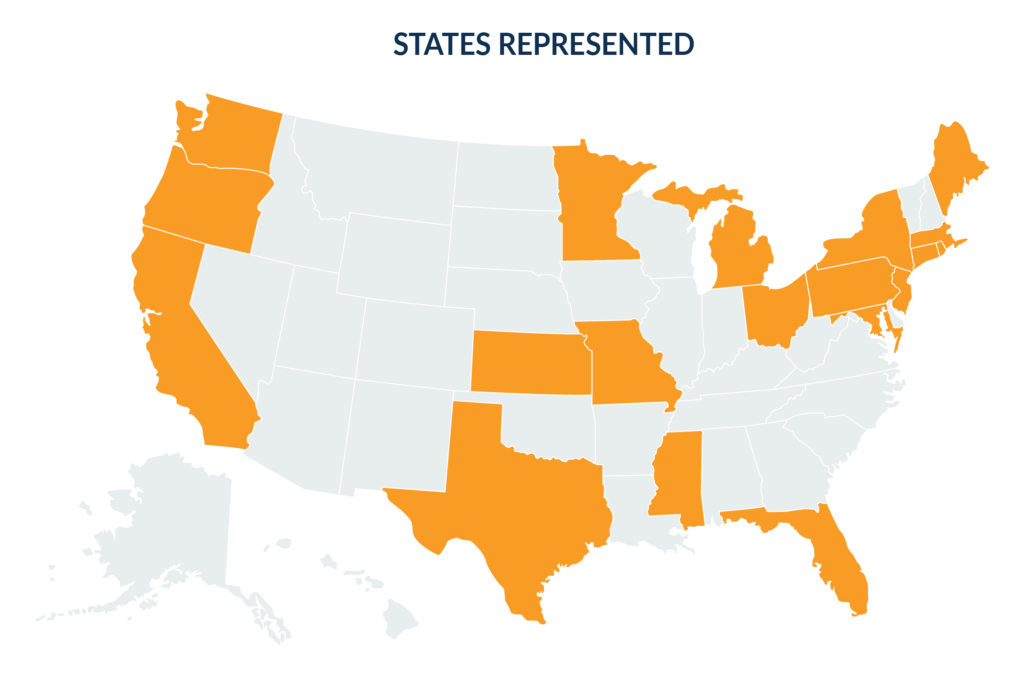

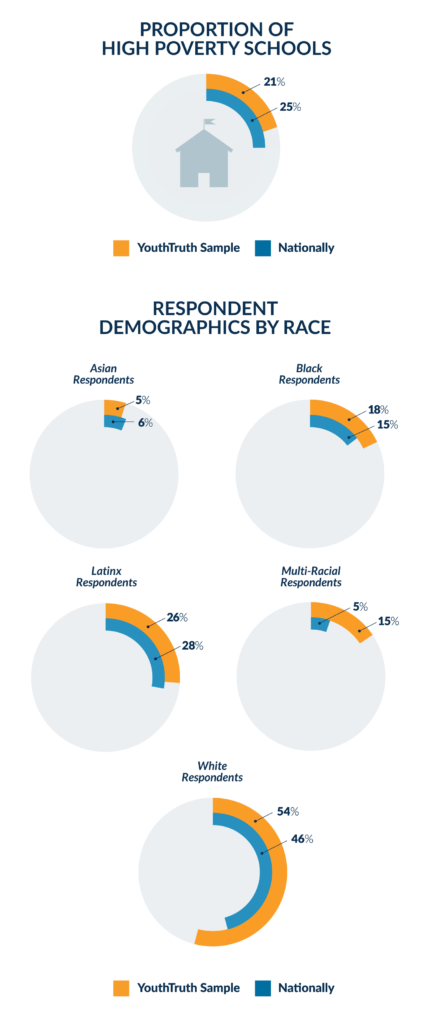

In spring 2021, 153,475 secondary students (grades 6–12) and 53,910 upper elementary students (grades 3–5) shared their perceptions of school and learning through YouthTruth’s research-based and anonymous 15-minute online survey. The survey was administered in both English and Spanish in partnership with 585 schools across 19 states.

The full set of data explored in this report is drawn from survey responses from 684,356 secondary students across four time periods: “Pre-COVID” (Fall 2010 to Fall 2019), “Spring 2020” (May and June 2020), “Fall 2020” (September to December 2020), and “Spring 2021” (January to May 2021).

Student voices represented in spring 2021 are from a mix of urban (29 percent), suburban (52 percent), and rural (14 percent) settings. Information not available for the remaining five percent. Respondent demographics by race, for students who chose to self-identify their race/ethnicity (76 percent), are shown at right.

Methodology

Methodology

Quantitative Data Analysis

The quantitative survey data were examined using descriptive statistics and a combination of independent t-tests, chi-squares, and effect size testing. An alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance, and effect sizes were examined for all analyses. Unless otherwise noted, only analyses with at least a small effect size are reported. To explore change over time a series of regressions were used, each controlling for student- and school-level characteristics across samples.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Throughout this report, you will find text-based and video-animated qualitative composite narratives that are drawn from analysis of more than 480,000 open-ended sentiments in the 2020–2021 academic year.

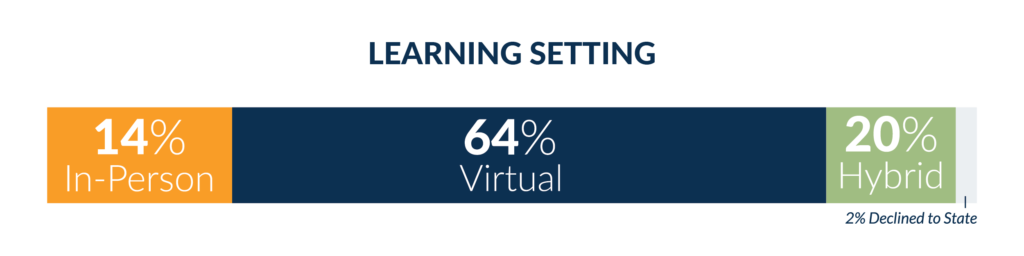

The open-ended comments were collected in response to as many as five questions: what students liked and disliked about school, and for students learning in a virtual environment, what students liked and disliked about learning from home. Students learning in a virtual setting were also asked what was challenging about learning at home and were invited to suggest ways their school could help. Except where noted otherwise, the analyses in this report primarily focused on the 271,852 open-ended high school student responses collected in spring 2021.

The process for analyzing this qualitative data began with a review of the codes established in our two earlier Students Weigh In reports, as well as the spring 2021 quantitative findings. Analytic questions were crafted to illuminate specific student demographic groups’ experiences. While we relied on our extant codes for lexical analysis, the approach remained data-driven and inductive.

Each narrative consists of sentiments from five to eight respondents and serves as a response to an analytic question. Where possible, we also sought to highlight actionable recommendations from students to adults. All composites received review for clarity and integrity.

2. Give Us Emotional and Mental Health [Video]

4. Danos Amabilidad Mientras Aprendemos tu Idioma

Give Us Kindness While We Learn Your Language

Jump to Key Findings

Finding One

While students’ perceptions of learning returned to pre-pandemic levels this spring, there is cause for concern about students’ social and emotional well-being. Students offer insights on how technology can help or hinder learning.

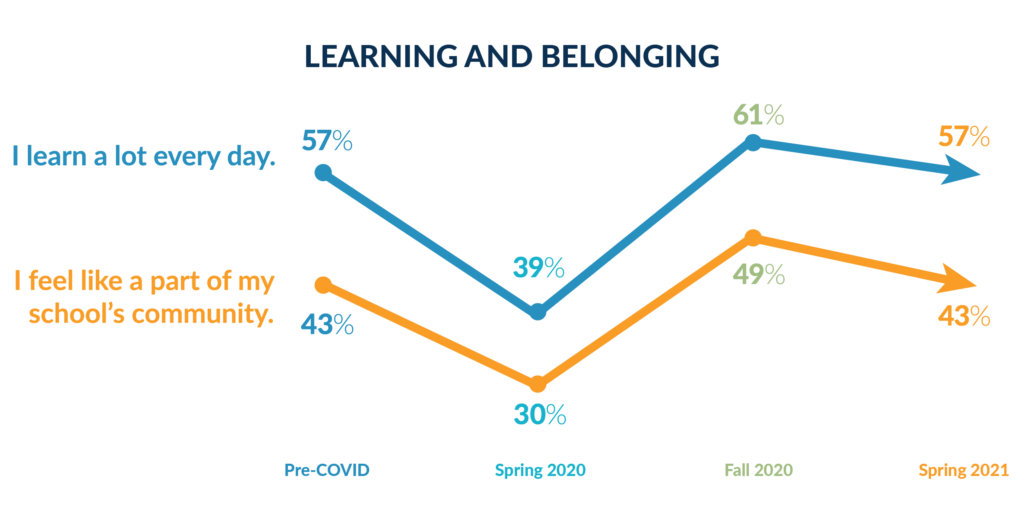

In the decade before the pandemic, 57 percent of students reported that they learned a lot every day, and 43 percent said that they felt like a part of their schools’ community. It was concerning, but surely no surprise, that in the transition to emergency distance learning these numbers dropped precipitously: 18 and 13 percentage points, respectively.

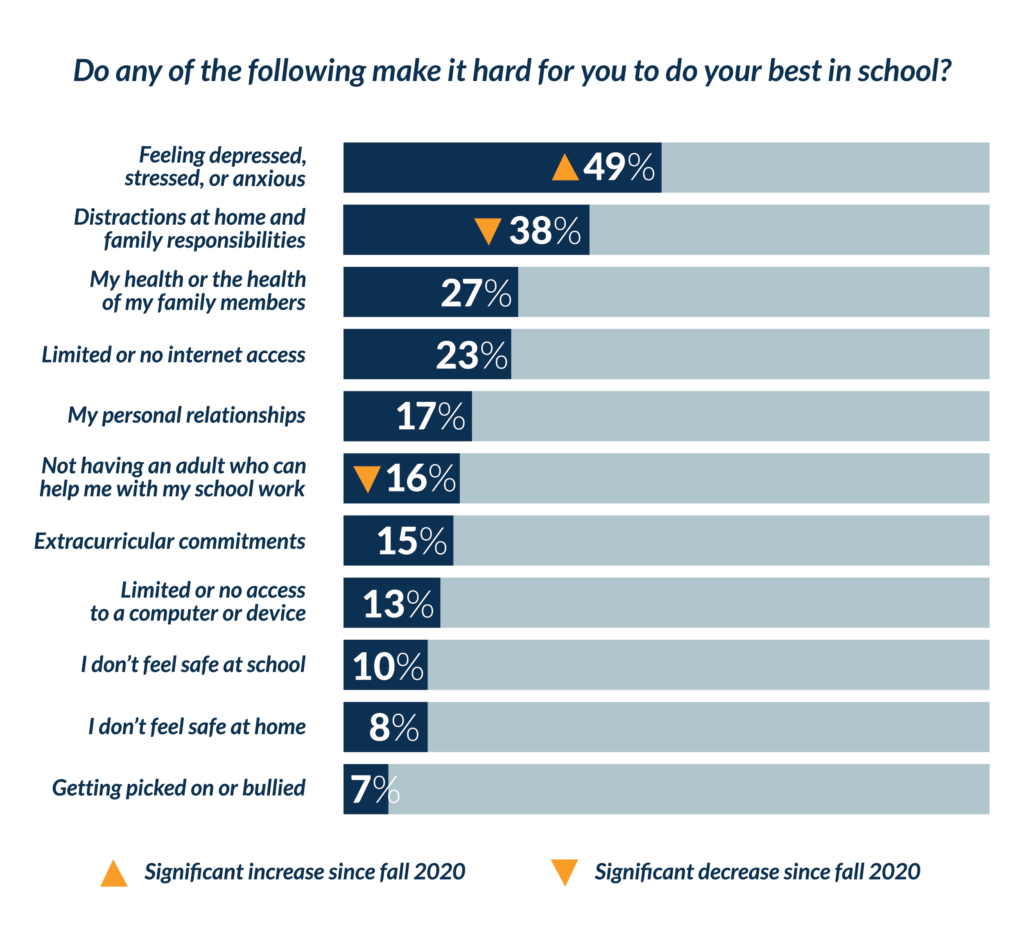

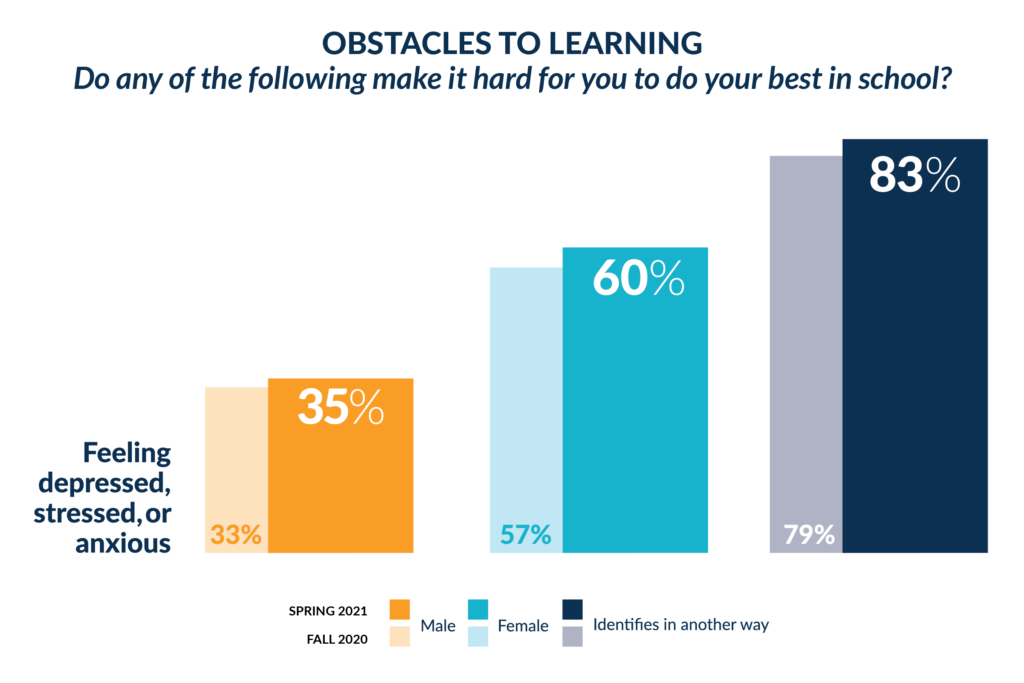

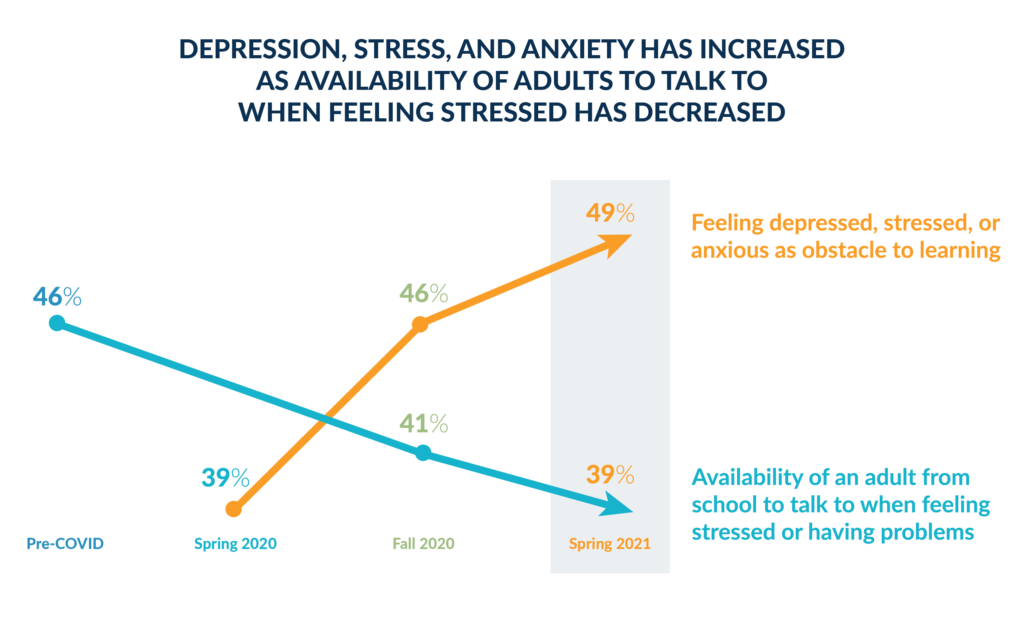

During the spring 2020 emergency school closures, amid the collective scramble to launch and support widespread virtual learning, more students reported Distractions at Home than any other obstacle to learning. In fall 2020, Feeling Depressed, Stressed, or Anxious eclipsed Distractions at Home and became the most frequently cited barrier to student learning, and then climbed even higher this spring. These results of depression and anxiety as significant barriers to student learning and well-being are in line with other recent research (see here, here, here, and here).

Females and students who identify in a way other than male or female continued to report in significantly higher numbers that feeling depressed, stressed, or anxious was an obstacle to learning, with nonbinary students reaching a worrying 83 percent. Students who are nonbinary or gender nonconforming are more at risk for suicide and self-harm. The Trevor Project’s most recent survey on LGBTQ mental health has found that the pandemic has made their lives even more stressful.

While fewer males cite feeling depressed, stressed, or anxious as an obstacle, a high school student in a recent YouthTruth workshop reminded us why mental health services and supportive relationships should be universal design elements in all schools to support all students. The school had recently experienced a suicide cluster. When the principal shared school-level data that echoed the findings above of greater mental health obstacles for females and students who identify as other than male or female, a student named Ezra wisely pointed out that boys learn “to downplay their feelings,” and he asked that his school “create more space for boys to open up.”

In Students’ Own Words

Give Us Emotional and Mental Health

When investigating how students describe stress, we encountered a chorus of student sentiments that described an overwhelming workload as school was reduced to an endless list of assignments.

In Solidarity

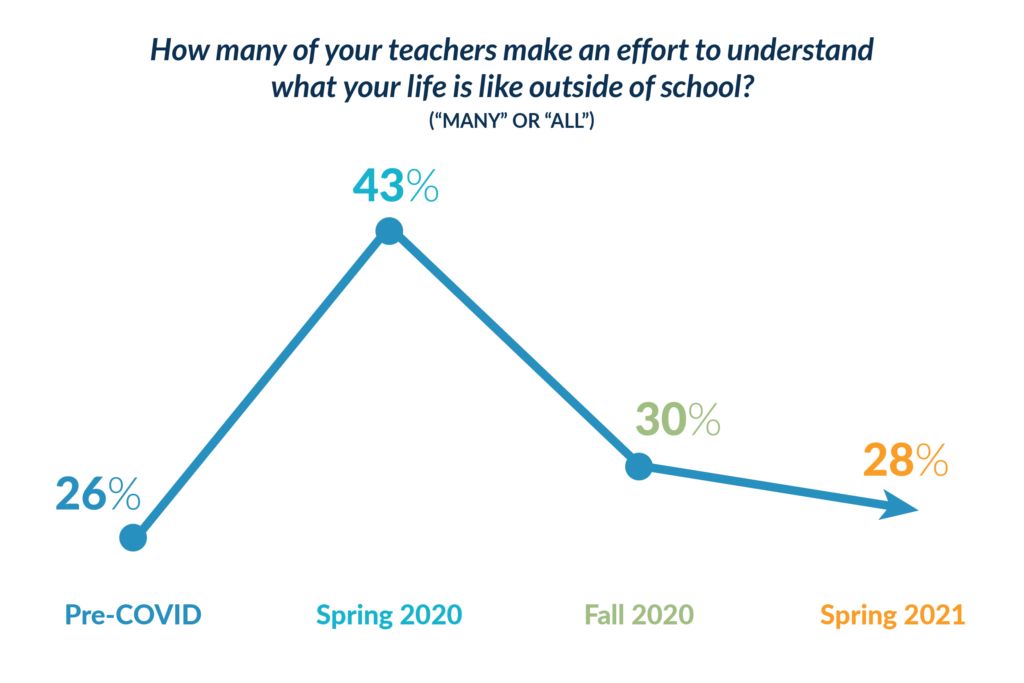

Many students detailed a new “solidarity” with their teachers, particularly those who demonstrated an understanding for students’ home lives and their individual challenges. These students felt trusted to “do good work,” and they valued the new ways of communicating with teachers.

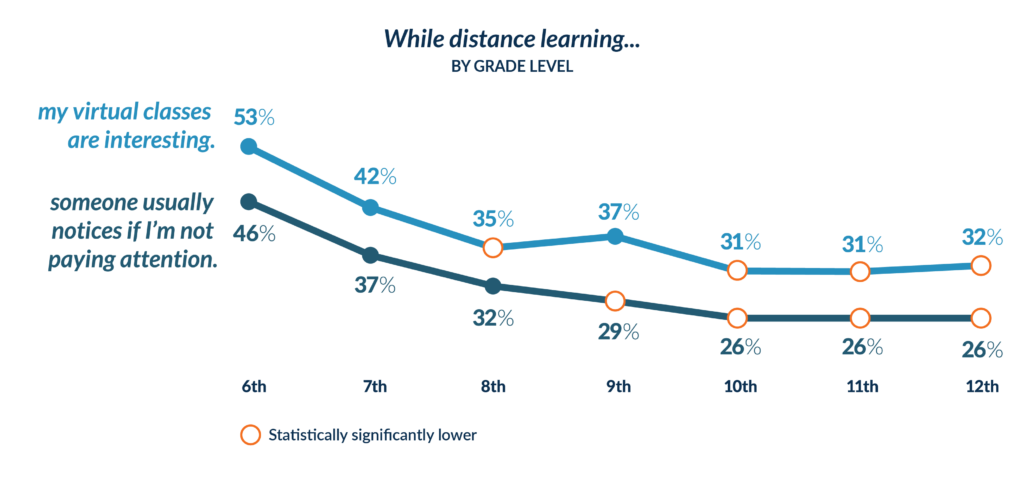

Just 37 percent of secondary students who learned virtually in the 2020–2021 academic year reported that their virtual classes were interesting, and only 31 percent of students said that someone noticed if they were not paying attention.

In Students’ Own Words

Please Understand: When Tech Hinders

Please Understand: When Tech Helps

Students also applauded specific favorable adaptations to online schooling that they hope will stay the same for in-person learning. In particular, many students reported high satisfaction with paper-free schooling, and they appreciated that teachers made it easy to access materials by posting them online.

Finding Two

The overall number of obstacles to learning for students is down. However, inequitable experiences and compounding barriers persist, especially for Black and Latinx learners.

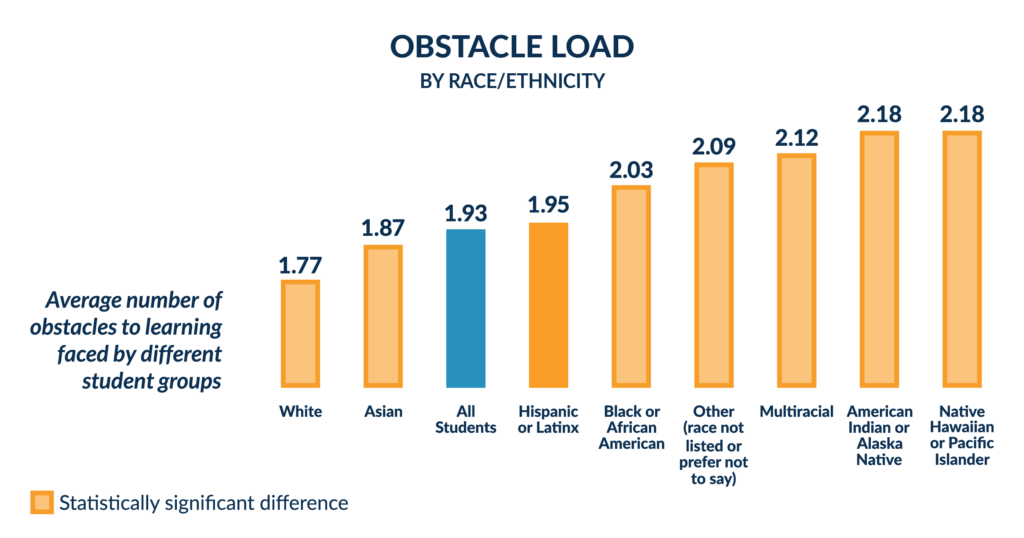

Some student groups faced compounding obstacles to their learning throughout the pandemic. We continue to investigate which groups of students faced more obstacles to learning through a simple “obstacle load” score, which is the average number of obstacles to learning faced by any given student. While it was heartening to see that the average obstacle load decreased from 2.14 in fall 2020 to 1.93 this spring, there are important differences between student groups.

When disaggregating the obstacle load score according to students’ race/ethnicity, we see similar equity and experience gaps to our fall findings in that white and Asian students experienced significantly fewer obstacles to learning than their non-white and non-Asian peers. However, Asian students as a group did not experience the benefit of the obstacle load decrease between last fall and spring this year. They were the only group whose obstacle load increased between fall and spring.

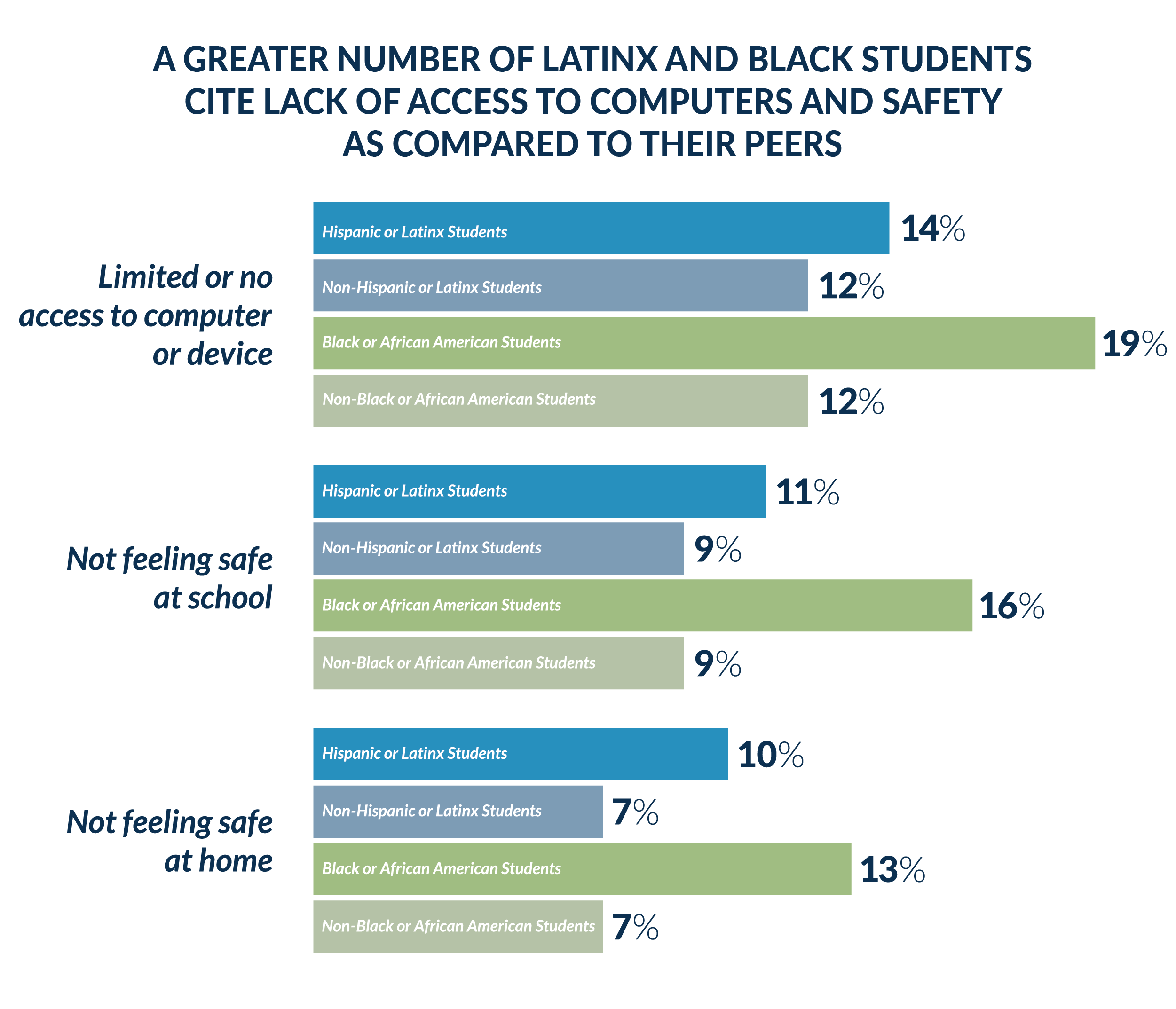

Recall the list of nearly a dozen potential obstacles to learning detailed in finding one. While not having access to a computer or device, not feeling safe at school, and not feeling safe at home were some of the least frequently cited obstacles that all students faced in spring. A greater proportion of Black or African American students faced these barriers as compared to their peers. The same is true for Hispanic or Latinx students.

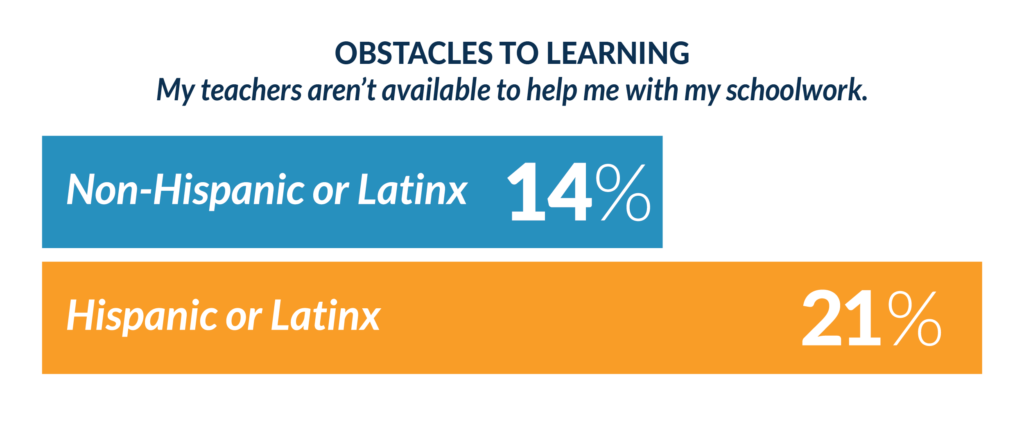

Compared to other students, Hispanic or Latinx students more frequently reported not having a teacher available to help with their schoolwork. Twenty-one percent of Hispanic or Latinx students cited lack of teacher support as an obstacle to learning as compared to just 14 percent of non-Hispanic or Latinx students.

A number of students described in their qualitative comments in Spanish an additional obstacle to learning that was not listed as a choice in our survey. For Spanish-speaking students, there was a bilingual or English language–learner burden to simply navigating the mechanics of the school day.

En las Proprias Palabras de los Estudiantes

In Students’ Own Words

Danos Amabilidad mientras Aprendemos tu Idioma

“Cuando entre el primer dia de escuela me humillaron porque no sabia ingles. No me siento agusto entrando a las clases y no entender nada por no entender el idioma. Aveces me duermo tarde por algunas tareas que no las entiendo y al otro dia tengo que despertarme temprano. Es que no puedo entender algunas cosas ya que están en inglés, pero creo que es más culpa mía. Aún no lo he aprendido muy bien y es difícil comunicarme tanto con maestros como con otros estudiantes. Mas aparte algunos maestros, no todos, cuando les pido un favor o les pregunto de tareas o de mis calificaciones me salen con otra cosa y enojados. Me gustaría que algunos maestros fueran más comprensivos. Quisiera más tiempo para los trabajos explicando mejor y dejando menos trabajos que tomen en cuenta que es difícil por no entender el idioma.”

English Translation: Give Us Kindness While We Learn Your Language

“My first day of class I was humiliated because I didn’t know English.” “I don’t feel comfortable going to classes and not understanding anything because I don’t understand the language.” “Sometimes I sleep late because I don’t understand some of the homework and the next day I have to wake up early.” “I just can’t understand some things since they are in English, but I think it’s more my fault.” “I have not learned [English] very well yet and it is difficult to communicate with both, teachers and other students.” Besides, “some teachers, not all, when I ask them for support or ask them about homework or my grades, they change the subject and [get] angry.” “I wish some teachers were more understanding.” I would like “more time for assignments, explaining them better and leaving fewer, taking into account that” it is difficult “due to not understanding the language”.

In Students’ Own Words

How do Black or African American students describe obstacles to learning, and what are their recommendations for improvement? As the pandemic intersected with the Black Lives Matter movement and the attempts by state legislatures to limit how schools teach about race, we wanted to understand how Black or African American students described their obstacles to learning.

Give Us Inclusive Curricula

There was a poignant theme among Black or African American students’ responses that owing to the absence of their history and meaningful engagement on current topics including racism, they were not inspired to learn.

Give Us Anti-Racist Policies

“I have teachers who value every race and person and go out of their way to make people feel comfortable sharing who they are and then I have teachers who don’t address it at all.” “The number of times that I hear people … say the N-word and just throw it around like it’s just an everyday thing, I find it to be quite insulting and I feel that no one is telling them the history of the word and why they SHOULDN’T say it.” “(I’ve been) picked on … for what I looked like or sounded like or even the color of my skin. Like how are YOU mad that I’M black? And when I tell the teachers they get mad and don’t do anything about it.” “There is no zero tolerance policy for racism. It feels like administration’s hands are always tied and there is no point sharing who is saying racist things because [the adults] did not hear it so they cannot help.” “You guys look the other way… like it didn’t happen. Like that’s not okay ya’ll really need to up your game up.”

Give Us Fair Treatment

“(Do) not pick on the black female students who are wearing shorts, and let the white female students who wear the same shorts be left alone.” “These Males that … walk around pants low and let everything show and it makes me mad that the girls come in fully clothed at times and still get dress coded.” “The dress code needs to be readjusted unless every student is being held accountable.” “Young girls need to stop getting sexualized.” “I want to be extremely honest here; I am not distracted by Ripped Jeans, I am not distracted by Sagging, I am not distracted by Crop Tops, I am not distracted by Tank Tops, I am not distracted by Leggings, I am not distracted by Flip Flops, I am not distracted by Skirts that are a couple of inches above the knee, I am not distracted by Untraditional Colored Hair.”

Finding Three

Students felt more respect from adults during the pandemic as well as increased academic support from teachers. However, respect and teacher support are experienced unevenly across student groups.

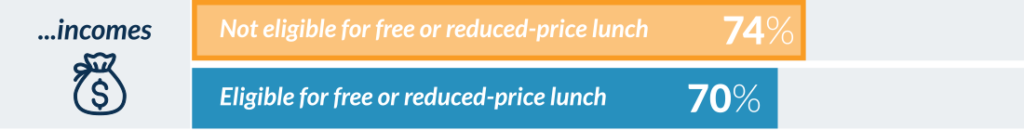

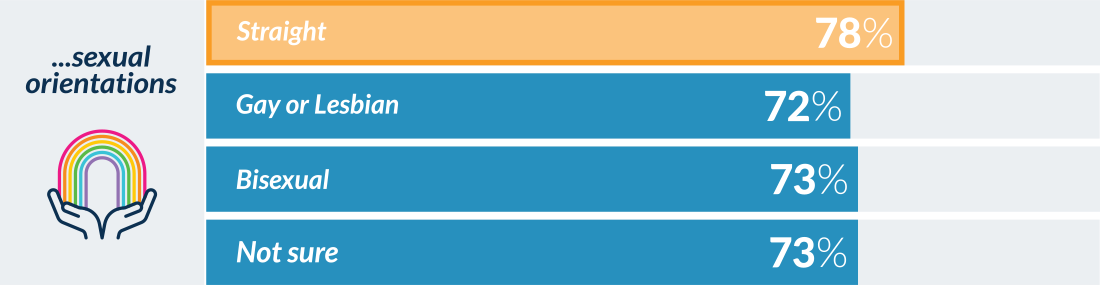

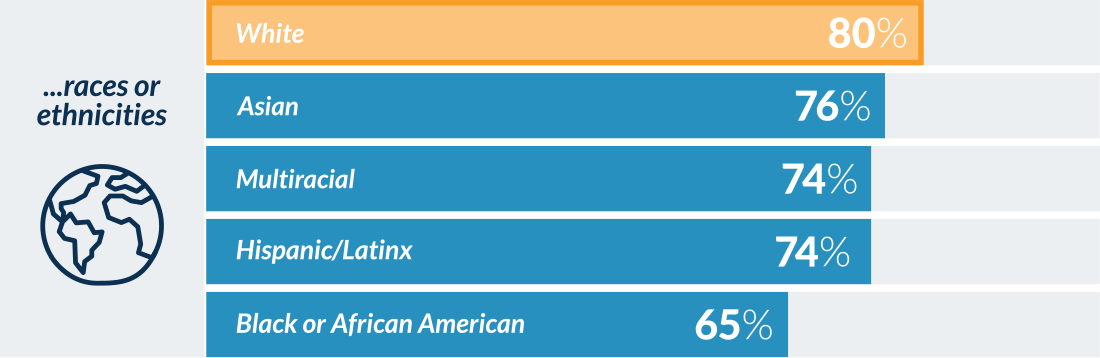

Across each question the majority of students—between 70 and 74 percent—agreed or strongly agreed that adults are respectful of people of different backgrounds. However, a higher proportion of students who belong to groups that have historically benefited from social and economic privilege perceive respect for various identities, as compared with students in groups that have historically been farthest from opportunity.

Adults from my school respect people from different

A higher percentage of students who do not qualify for free or reduced-price lunch agree that adults are respectful of people of different incomes, as compared to students who receive free or reduced-price lunch.

A slightly higher percentage of students who do not receive special education services agree that adults are respectful of people of different abilities; compared to students who do receive special education services.

A higher percentage of students who identify as straight agree that adults are respectful of people of different sexual orientations, as compared to students who do not identify as straight.

A higher percentage of students who identify as white agree that adults are respectful of people of different races and ethnicities, as compared to students who do not identify as white.

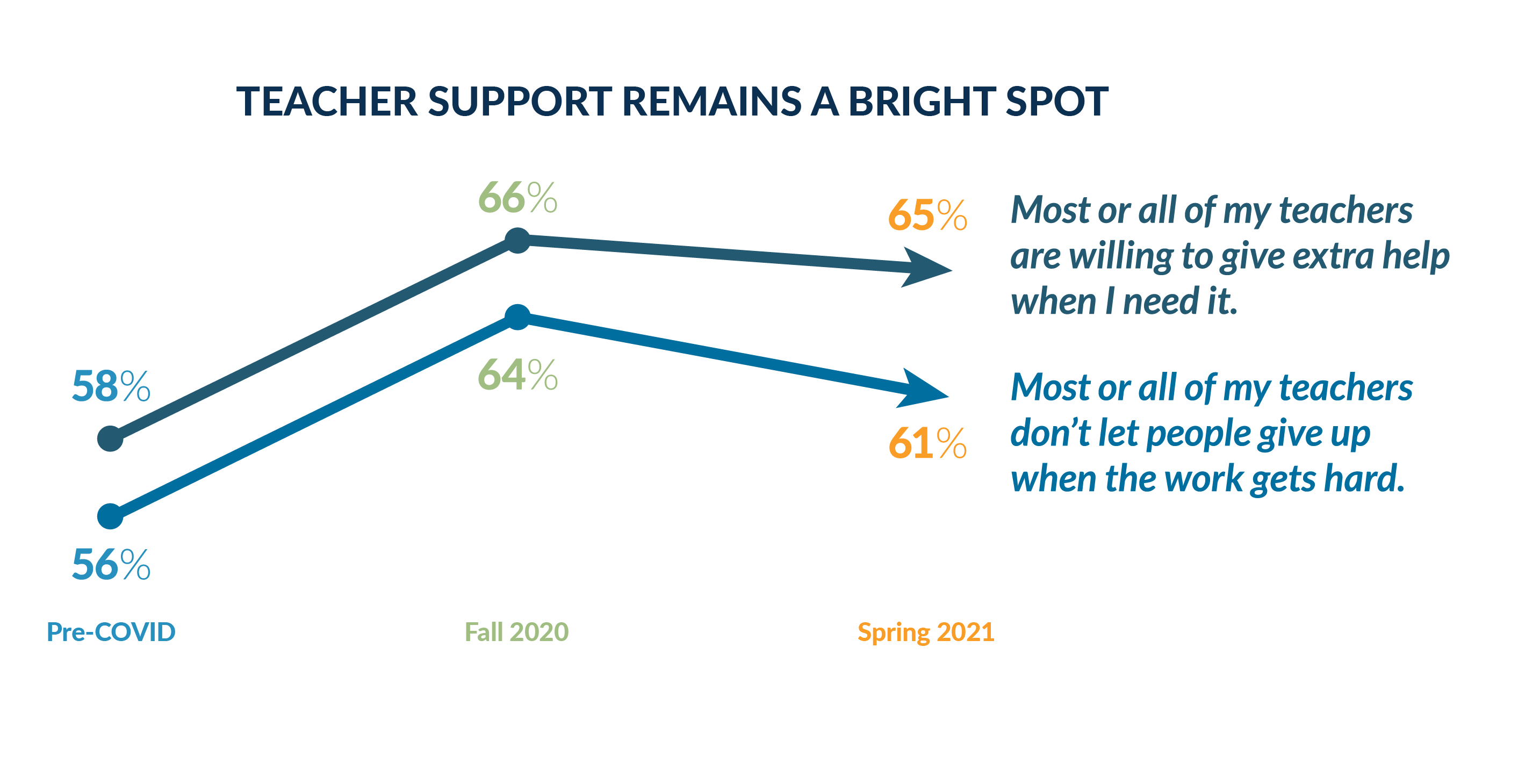

During the pandemic, students reported an improved sense that most of their teachers were willing to give them extra help when they need it as well as to not let people give up when work gets hard. As researchers have demonstrated, high schools with a high value-add to student work habits improve student academic outcomes. We are hopeful that these positive academic interventions may prove durable.

Finding Four

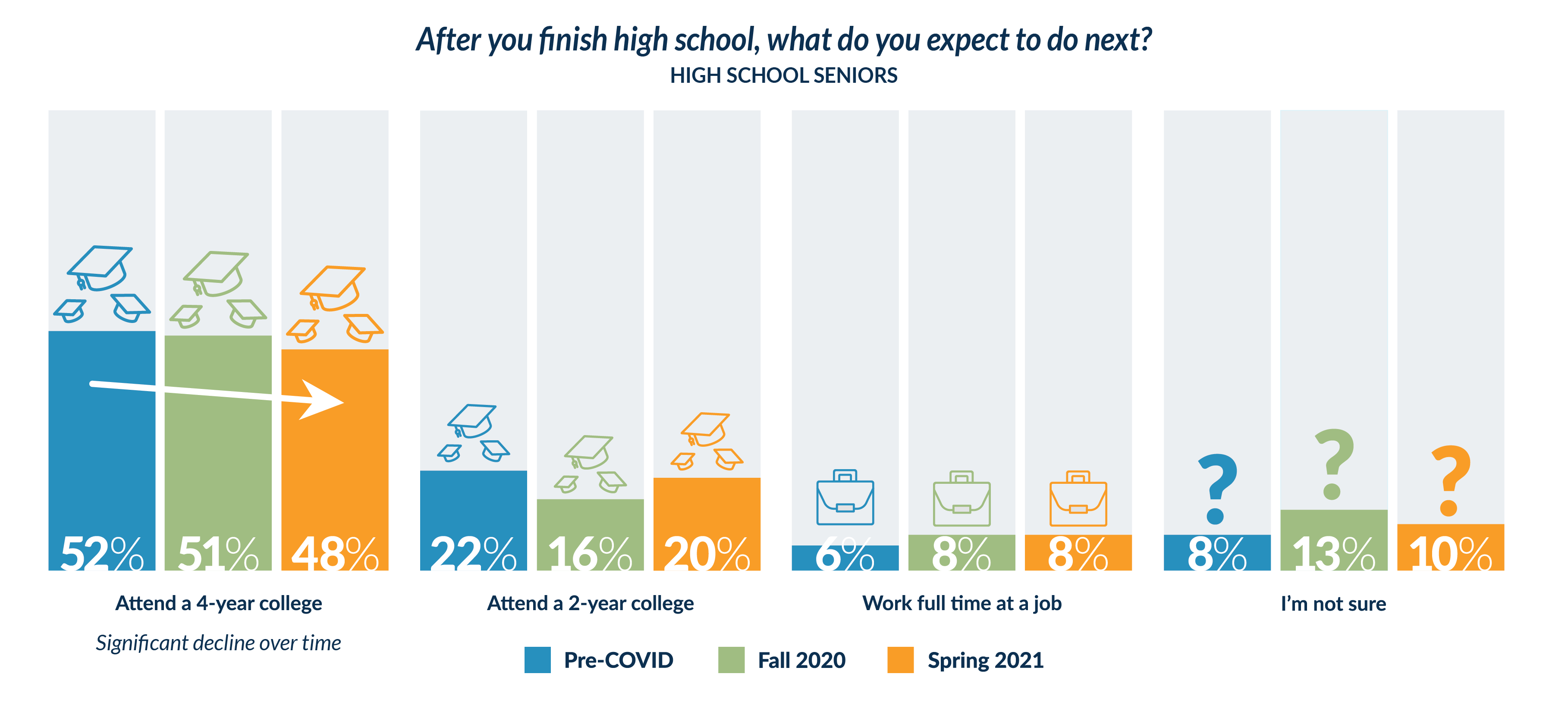

Fewer students plan to go to college. Students offer ideas for making access to higher education more equitable.

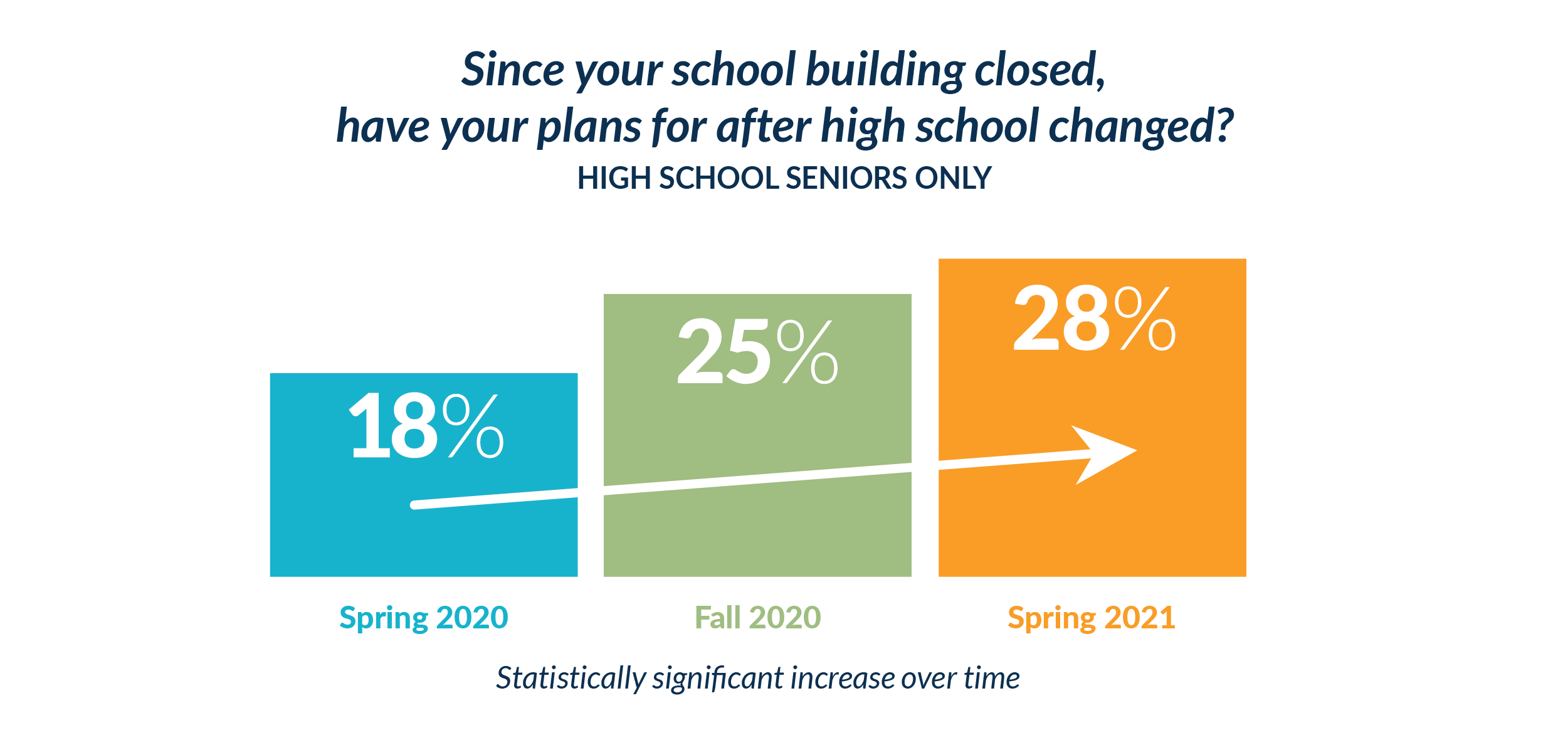

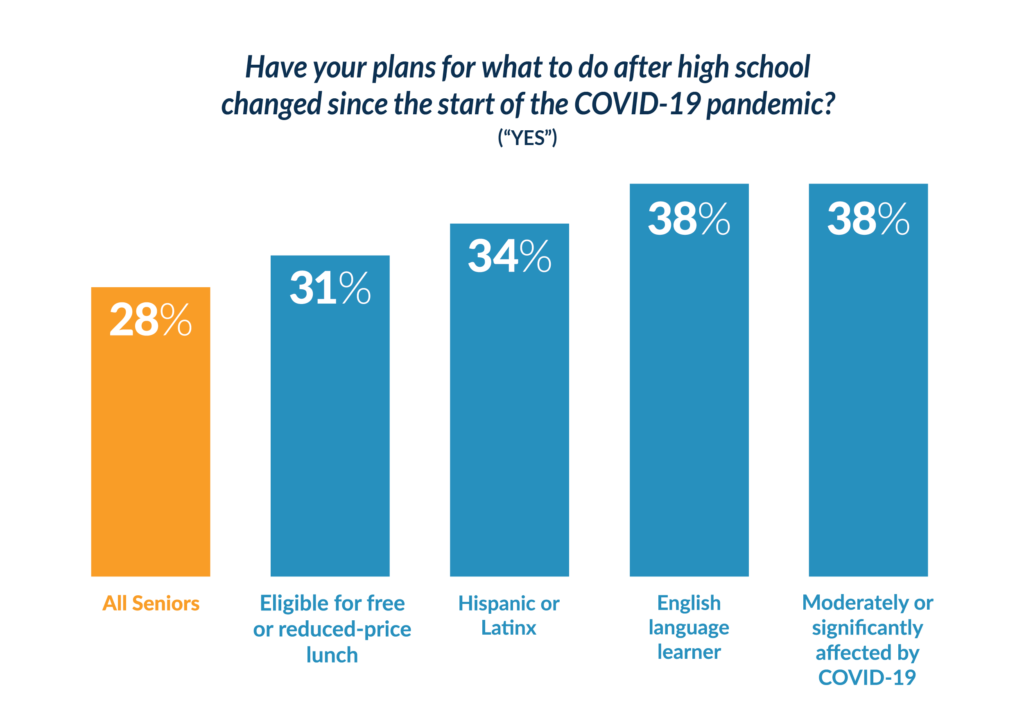

There has been widespread concern as college enrollments have dropped over the course of the pandemic, an indicator that for many, college-going plans have been derailed. This trend was also evident in our data.

The percentage of seniors planning to attend four-year and two-year colleges declined in 2020 and remained lower than pre-pandemic levels in spring 2021. In particular, the percentage of seniors this spring who reported that they plan to attend a four-year college dropped to below half, to 48 percent. This is an important signal for higher education enrollment predictions. As the National Student Clearinghouse recently reported, colleges recorded a near six percent drop in undergraduate enrollment this spring, the “steepest decline so far since the pandemic began.”

In Students’ Own Words

Give Us Practical Guidance

Many seniors who reported a change in plans this spring explained that they did not have access to the support needed to navigate the application process, and there was a plaintive refrain among the comments of students asking for help.

Give Us Pathways for the Future

Many of these students also expressed frustration at the lack of access to career and technical pathways, and they described how traditional academic subjects seemed esoteric or irrelevant in the midst of the pandemic.

Conclusion

As the United States continues to navigate new COVID-19 variants, vaccine adoption, and what they mean for schools’ ongoing operations and staffing, there is a critical opportunity now to listen directly to K-12 students and use their feedback in continuous improvement practices.

As we’ve seen in this report, many aspects of students’ experience of school are returning to pre-pandemic levels and may be perceived as a salutary marker. However, when we investigate the unequal experiences across student groups and listen to how students characterize their perceptions in their own words, it is clear that students still face formidable challenges. We also learn in this report that students offer actionable feedback about how and where to target support, and students seek partnership with adults in creating solutions. Finally, this data prompts important questions about what we’ve learned during this period and what we will choose to take with us into the future.

As educators and education funders continue to make progress supporting students’ social, emotional, and academic development – even in these uniquely difficult times – it is imperative that we perpetually tune into the voices and experiences of those for whom the education system is designed for: students.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for their support of this report and the second report in the Students Weigh In series. We would also like to thank the following foundations for their support of the first report in this series: William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Walton Family Foundation, and Carnegie Corporation of New York. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the foundations.

Thank you to our volunteer student voice composite memo readers: Jonathan (“Give us Emotional and Mental Health”), Robert (“Give us Inclusive Curricula”), Noah (“Please Understand: When Tech Hinders”), and Lola (“Give Us Pathways for the Future”), as well as the team at Scope & Sequence for the animated video collaboration.

This work would not be possible without the partnership of the hundreds of schools that elevate student voices within their local communities and the more than half a million students who have shared their insights and expertise by weighing in.