When designed and implemented well, discipline policies and practices can help a school run smoothly, support teachers, and set up equitable conditions of learning. When managed poorly, however, school discipline policies and practices can have serious long and short term effects on students’ lives both inside and outside the classroom, including contributing to the school to prison pipeline. Anonymous feedback from school stakeholders allows educators real-time insights into how fair discipline is in the eyes of those closest to the issue: students, family, and staff themselves.

Today we released a new report that explores anonymous survey data collected from over 104,000 students, family, and staff about discipline and fairness in 132 schools across the country. As a national nonprofit committed to elevating student and stakeholder voices on critical issues in education, we wanted to know: what do students, families, and school staff think about discipline and fairness at their school?

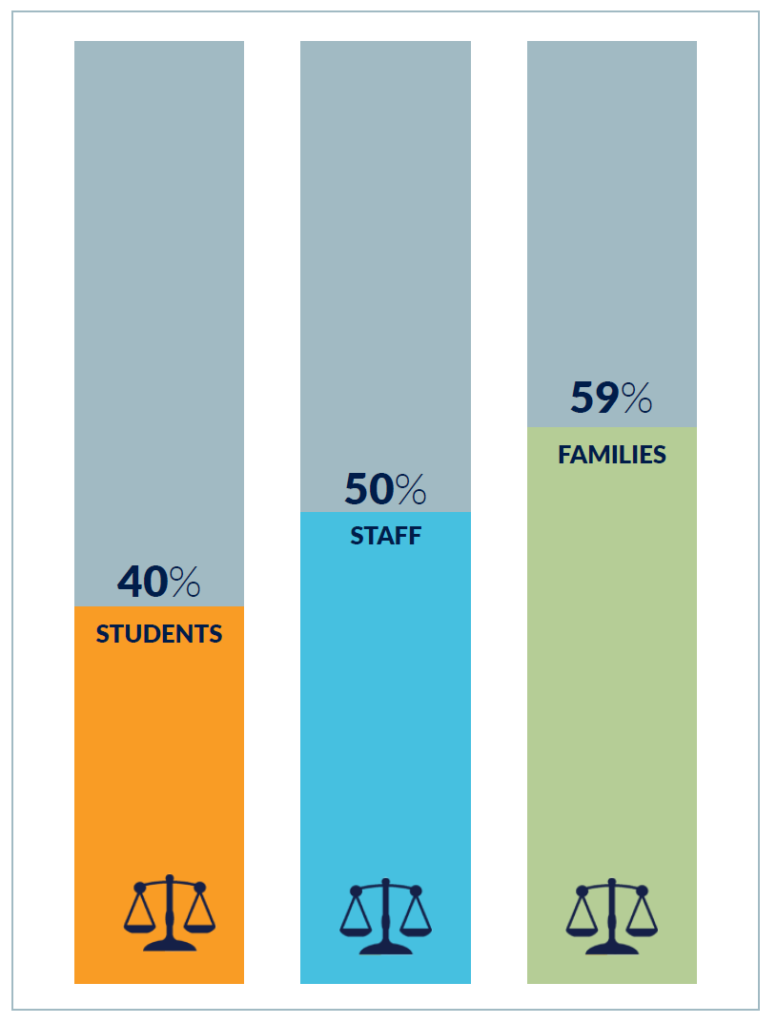

Our findings reveal that, overall, students feel less positively about discipline than do families or staff. Less than half of students – 40 percent – feel discipline at their school is fair, compared to 59 percent of family members and 50 percent of staff members.

Although less than half of students feel school discipline is fair, when students feel more positively about discipline, families and staff tend to agree. In our analysis, a temperature check with one stakeholder group is a good indicator of how other stakeholders feel about the fairness of school discipline. Of the “top performing” schools in the eyes of students (that is, the top 25 percent of schools in our sample based on student ratings of discipline), 69 percent are “above typical” in the eyes of parents and guardians (that is, in the top half of schools in our sample based on family members’ ratings of discipline). Results for staff perceptions compared to top performing schools in the eyes of students were similar to those of family members.

Our data also show that while there is not one racial or ethnic group that has a consistently more or less positive experience with school discipline across stakeholders, differences across race/ethnicity exist within each stakeholder group. A closer look shows that Asian students rate discipline at their school more positively than do other racial or ethnic groups, while Multiracial students rate discipline at their school less positively. (African American or Black students’ ratings are a few percentage points lower than other students’ ratings, but the difference observed in our sample was not statistically meaningful.)

For families, Hispanic and Asian parents and guardians rate school discipline somewhat more positively than do other parents and guardians, while White parents and parents who preferred not to identify their race or ethnicity rate school discipline less positively. School staff who preferred not to say their race or ethnicity also feel less positively about school discipline.

“Despite advocacy at the local, state, and federal levels, according to the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, students of color are still disproportionately affected by inconsistencies in school discipline policy,” says Jen Wilka, the YouthTruth team’s executive director. “Triangulating perceptions and experiences of school discipline across stakeholder groups, and subgroups within those groups, can help educators discover what aspects of discipline policies and practices are truly working, and for whom.”

Our report also reveals less positive perceptions of the fairness of discipline among high school students and families as compared to their middle school counterparts, and less positive feelings about discipline for staff members who have five or more years of tenure at their school versus those who have been at their school for less than five years.

There was no meaningful difference in the perception of student, family, and staff members at high poverty schools — schools in which at least 70 percent of students receive free or reduced-price lunch — versus at schools that are not high poverty. Likewise, individual family or student’s free or reduced-price lunch eligibility was not associated with a difference in student or family ratings of discipline.

So, once we know where we need to improve, what are some next steps for educators?

Keep asking – and keep listening. If you’re a superintendent, principal, or a school staff member, sharing feedback data back with your school communities can add a more nuanced understanding of what is working and what isn’t, in addition to increasing school-wide buy-in when it comes to making change. For protocols and strategies to help get stakeholders more involved in making data actionable, check out this YouthTruth guidebook.

Make the data actionable. Luckily, once we know how we’re doing when it comes to discipline, there are a lot of resources to help make schools successful in supporting and managing student behavior. PromotePrevent’s resources on Positive School Discipline, the Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports guide from PBIS, and The National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments are just a few worth checking out.

Asking students, families, and school staff anonymously and directly about their perceptions of and experiences with discipline is a quick and powerful way to “temperature check” what’s going well and where improvements are needed to keep discipline positive and fair. ![]() Triangulating perceptions and experiences of school discipline across these three groups can help educators discover what aspects of discipline practices and policies are truly working, and for whom.

Triangulating perceptions and experiences of school discipline across these three groups can help educators discover what aspects of discipline practices and policies are truly working, and for whom.

Read, download, and share the full report here.